Self-Advocacy

“I am convinced that we must listen to a far greater degree to the individuals with handicaps.”

Please note: Some of the words used here are old and are not used anymore because they are hurtful and mean.

For their entire career, Gunnar and Rosemary had been successful because they knew how to find proof that disabled people were being treated badly. As a lawyer, Gunnar knew that politicians and judges had to be given proof so that they could not ignore him. He was so successful that they had listened and led to major change. In the 1960s and 1970s, the government made rules and created jobs to make sure disabled people could get an education and live in the community. But Gunnar was worried. The proof he had used was often given to him by non-disabled people, like the relatives of disabled people who were being kept as inmates in big state institutions.

In June 1985, Gunnar wrote a one-page statement of his beliefs—a “Credo”—that shows how much his views about proof had changed, and why.

As Gunnar began to see change happen, he became very worried that the people who were taking the new jobs and writing the new rules were using their power to tell disabled people what they should be rather than supporting their wishes to become who they wanted to be. The Credo shows that he thought that non-disabled people believed numbers and tests could tell them everything about who a person was, and that this was wrong. While they thought they were helping, Gunnar thought they were using these things to hold disabled people back.

For example, he was also very upset that all the new rules, jobs, and organizations that were being created to support disabled people used big, complex words instead of plain language. He worried that all the big words made it impossible for disabled people to do things for themselves and understand things for themselves. This idea was ahead of its time.

But perhaps most of all, Gunnar thought that a lot of the non-disabled people who said they wanted disabled people to have rights were not willing to see disabled people as friends and equals and just share a meal with them.

Gunnar’s views had clearly changed, and that was no accident. In the early 1970s, he was introduced to intellectually disabled people who were leading the fight for their own rights in Oregon and Washington. Their movement was called the People First movement and today they are called self-advocates. Their movement soon grew to become an international one. Gunnar was inspired and after a lifetime of being a leader of parents and advocates who supported disabled people, he became a follower of disabled leaders; the self-advocates.

The Dybwad collection contains handwritten documents, notes, photographs, and papers from his work during this time. These documents show how Gunnar and Rosemary spent these later years in their lives working for self-advocates. They did this by working tirelessly to make sure that non-disabled people understood what self-advocates were doing and why they should support their efforts. One example from the archive are drafts of a speech where Gunnar credits Bernard Carabello, a self-advocate who had fought his way out of the Willowbrook State School in New York, with challenging him and changing his way of thinking.

In this video, Carabello talks about Gunnar in those early days of self-advocacy.

One of the leaders of the self-advocacy movement in Massachusetts is Anne Fracht, who was a co-founder of the self-advocacy group Mass Advocates Standing Strong with her longtime partner Craig Smith. In this video, Fracht describes Gunnar’s fifth and most cherished credo; sharing home, a meal, and time with the Dybwads.

Until Rosemary’s death in 1992 and Gunnar’s death in 2001, they fought to support the goals of self-advocates like Carabello and Fracht.

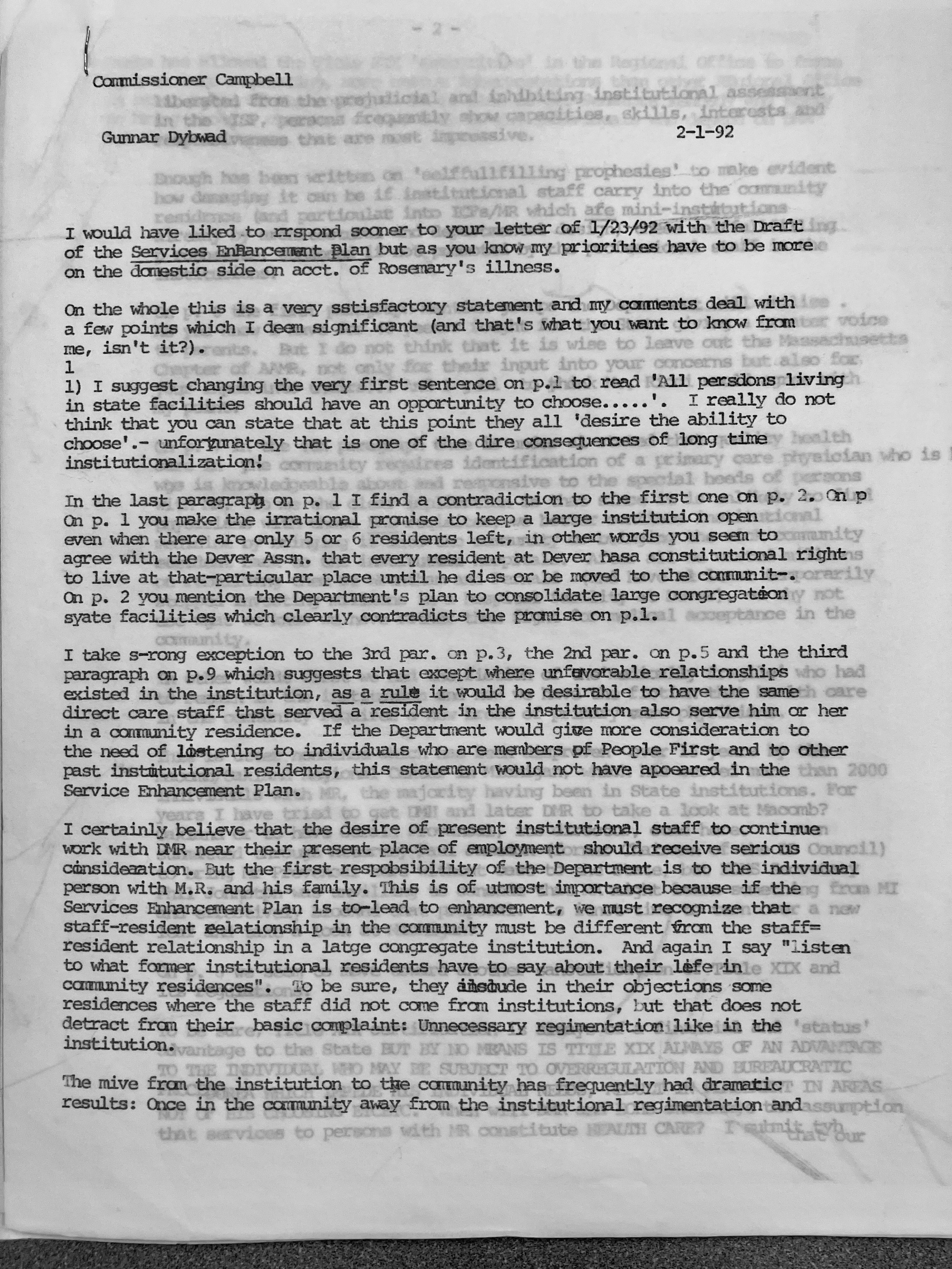

For example, in this February 1, 1992 letter to the Massachusetts Commissioner for the Department of Mental Retardation, Gunnar is reviewing the state’s proposed “Services Enhancement Plan” He writes

“I take s[t]rong exception to [the wording] which suggests that except where unfavorable relationships existed in the institution, as a rule it would be desirable to have the same direct care staff that served a resident in the institution also serve him or her in a community residence. If the Department would give more consideration to the need of listening to individuals who are members of People First and to other past institutional residents, this statement would not have appeared in the Service Enhancement Plan.”